In the introduction to the course day we talked about the process so far and what would need to be done more to get a full server.

The students came up with the following list:

- Securing SSH (disable password login)

- Securing Apache (installing an SSL certificate)

- Get a real SSL certificate from Let’s Encrypt and automatically update it.

- Install a full web server with PHP and database support

The three security related topics will be discussed in this post. The ‘LAMP-installation’ will follow in the next post.

SSH remove password:

Login with SSH to your server, this should not ask for a password, as we have setup public-key authentication.

Use your favorite editor to edit the sshd_config file

sudo vi /etc/ssh/sshd_config

Find the following line:

PasswordAuthentication yes

And change it to:

PasswordAuthentication no

If there is a # at the beginning of that line, remove that #. An # sign comments out a line, so it is not used.

Save the file restart the SSH service using this command:

sudo systemctl restart ssh

Check in a separate terminal if you can still login to the Pi using SSH.

If all went well, you have secured SSH on you Pi.

HTTPS:

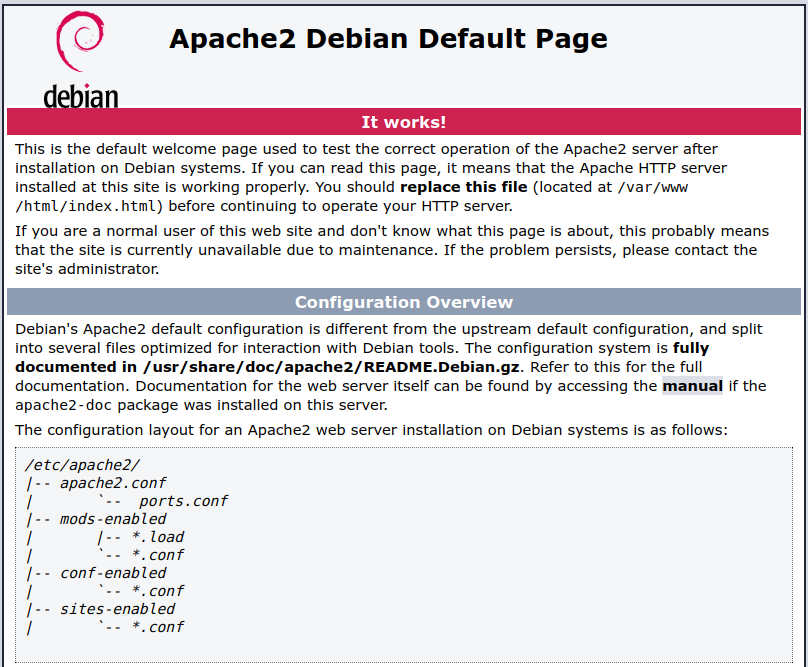

To create a secure webserver you need to enable SSL in your webserver software. In this example we use Apache.

First we need to to create a SSL certificate we will use. For this, we create a folder to save these certificates in:

sudo mkdir /etc/apache2/ssl

sudo openssl req -x509 -nodes -days 1095 -newkey rsa:2048 -out /etc/apache2/ssl/server.crt -keyout /etc/apache2/ssl/server.key

Fill in the form that start, you can also press enter on every option to accept the default, as we will shortly replace these values with the Let’s Encrypt certificates.

Then enable the SSL module using the following command:

sudo a2enmod ssl

Then you need to setup the correct settings in de configuration file and enable the SSL site by creating a symbolic link . We change the two lines relative to SSLCertificate as follow :

SSLCertificateFile /etc/apache2/ssl/server.crt

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/apache2/ssl/server.key

sudo nano /etc/apache2/sites-available/default-ssl.conf

sudo ln -s /etc/apache2/sites-available/default-ssl.conf /etc/apache2/sites-enabled/000-default-ssl.conf

Lastly restart apache servers:

sudo systemctl restart apache2

You can navigate in a browser to your secure website: https://[yourname].duckdns.org

You will notice you get a warning about the certificate we have just created. By default self signed certificates are not considered safe, as the creator of the certificate cannot be verified. To fix that we’ll get to the next part:

LET’S ENCRYPT Certificate

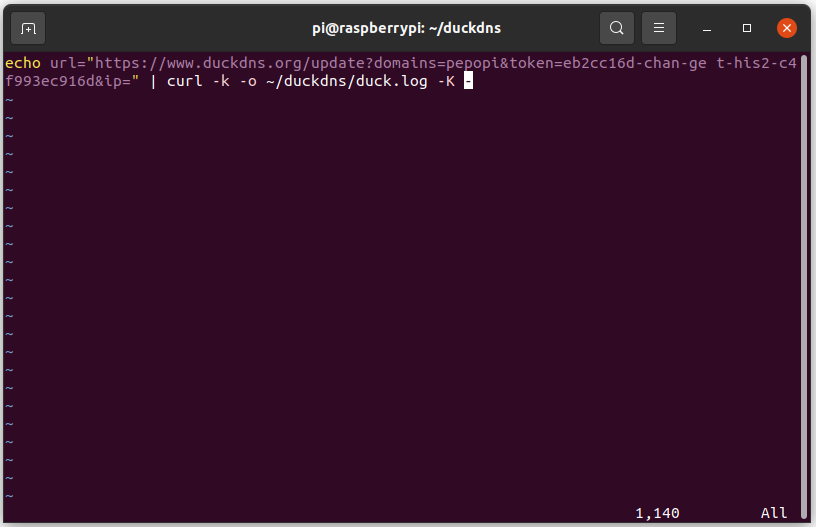

Let’s Encrypt is an organization that allows you to create a valid certificate. It is valid for 3 months, to not have to manually update this every 3 months a script will be enabled to do this for us.

First we need to install a few packages:

sudo apt install certbot python3-certbot-apache

Certbot is looking for a few specific directives in the configuration file, so we make sure they are there: (Make sure to replace [your_domain] in this command!)

sudo vi /etc/apache2/sites-available/[your_domain].conf

and edit the following lines to match your domain name ([yourname].duckdns.org)

...

ServerName your_domain

#ServerAlias www.your_domain ## Optional

...

Test your configuretion and if you get a Syntax OK you can restart Apache2:

sudo apache2ctl configtest

sudo systemctl reload apache2

Now we can generate the actual certificates:

sudo certbot --apache

Fill in the questions asked by the script and let it generate they certificates (Choose 2: Redirect if asked)

Once done you can go to your website to check if it all worked as expected.

The last thing we do is check if the auto renew of the certificate works. I has been setup as a cron job by copying a script to /etc/cron.d when certbot was installed.

Check if the service is available and you can do a dry run:

sudo systemctl status certbot.timer

sudo certbot renew --dry-run

Your apache server is ready foor https access.

Used sources:

- https://linuxhandbook.com/ssh-disable-password-authentication/

- https://hallard.me/enable-ssl-for-apache-server-in-5-minutes/

- https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-secure-apache-with-let-s-encrypt-on-ubuntu-20-04