Before we continue it is good to get a bit of background information on which files you can expect to find at which part of the file system:

| / | The root directory, where everything begins. |

| /bin | Contains binaries (programs) that must be present for the system to boot and run. |

| /boot | Contains the Linux kernel, initial RAM disk image (for drivers needed at boot time), and the boot loader. Interesting files include /boot/ grub/grub.conf, or menu.lst, which is used to configure the boot loader, and /boot/vmlinuz (or something similar), the Linux kernel. |

| /dev | This is a special directory that contains device nodes. “Everything is a file” also applies to devices. Here is where the kernel maintains a list of all the devices it understands. |

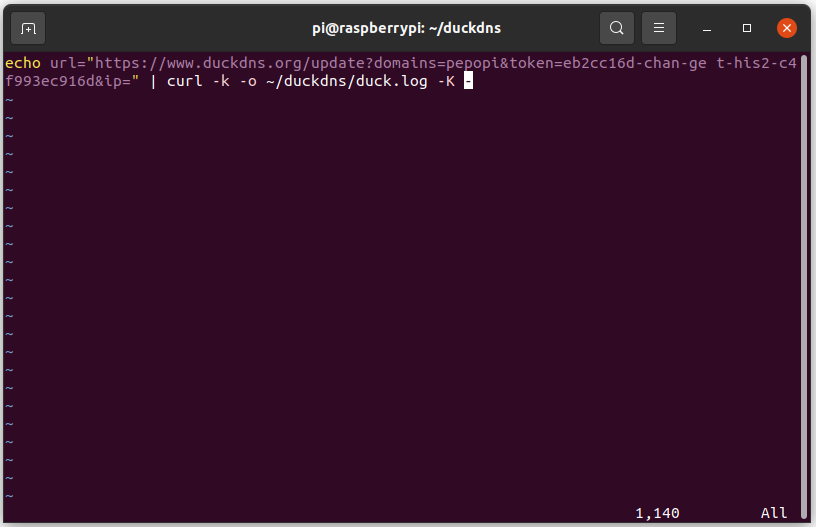

| /etc | The /etc directory contains all the system-wide configuration files. It also contains a collection of shell scripts that start each of the system services at boot time. Everything in this directory should be readable text. While everything in /etc is interesting, here are some all-time favorites: /etc/crontab, a file that defines when automated jobs will run; /etc/fstab, a table of storage devices and their associated mount points; and /etc/passwd, a list of the user accounts. |

| /home | In normal configurations, each user is given a directory in /home. Ordinary users can write files only in their home directories. This limitation protects the system from errant user activity. |

| /lib | Contains shared library files used by the core system programs. These are similar to dynamic link libraries (DLLs) in Windows. |

| /lost+found | Each formatted partition or device using a Linux file system, such as ext3, will have this directory. It is used in the case of a partial recovery from a file system corruption event. Unless something really bad has happened to your system, this directory will remain empty. |

| /media | On modern Linux systems, the /media directory will contain the mount points for removable media such as USB drives, CD-ROMs, and so on, that are mounted automatically at insertion. |

| /mnt | On older Linux systems, the /mnt directory contains mount points for removable devices that have been mounted manually. |

| /opt | The /opt directory is used to install “optional” software. This is mainly used to hold commercial software products that might be installed on the system. |

| /proc | The /proc directory is special. It’s not a real file system in the sense of files stored on your hard drive. Rather, it is a virtual file system maintained by the Linux kernel. The “files” it contains are peepholes into the kernel itself. The files are readable and will give you a picture of how the kernel sees your computer. |

| /root | This is the home directory for the root account. |

| /sbin | This directory contains “system” binaries. These are programs that perform vital system tasks that are generally reserved for the superuser. |

| /tmp | The /tmp directory is intended for the storage of temporary, transient files created by various programs. Some configurations cause this directory to be emptied each time the system is rebooted. |

| /usr | The /usr directory tree is likely the largest one on a Linux system. It contains all the programs and support files used by regular users. |

| /usr/bin | /usr/bin contains the executable programs installed by your Linux distribution. It is not uncommon for this directory to hold thousands of programs. |

| /usr/lib | The shared libraries for the programs in /usr/bin. |

| /usr/local | The /usr/local tree is where programs that are not included with your distribution but are intended for system-wide use are installed. Programs compiled from source code are normally installed in /usr/local/bin. On a newly installed Linux system, this tree exists, but it will be empty until the system administrator puts something in it. |

| /usr/sbin | Contains more system administration programs. |

| /usr/share | /usr/share contains all the shared data used by programs in /usr/bin. This includes things such as default configuration files, icons, screen backgrounds, sound files, and so on. |

| /usr/share/doc | Most packages installed on the system will include some kind of documentation. In /usr/share/doc, we will find documentation files organized by package. |

| /var | With the exception of /tmp and /home, the directories we have looked at so far remain relatively static; that is, their contents don’t change. The /var directory tree is where data that is likely to change is stored. Various databases, spool files, user mail, and so forth, are located here. |

| /var/log | /var/log contains log files, records of various system activity. These are important and should be monitored from time to time. The most useful ones are /var/log/messages and /var/log/syslog. Note that for security reasons on some systems, you must be the superuser to view log files. |

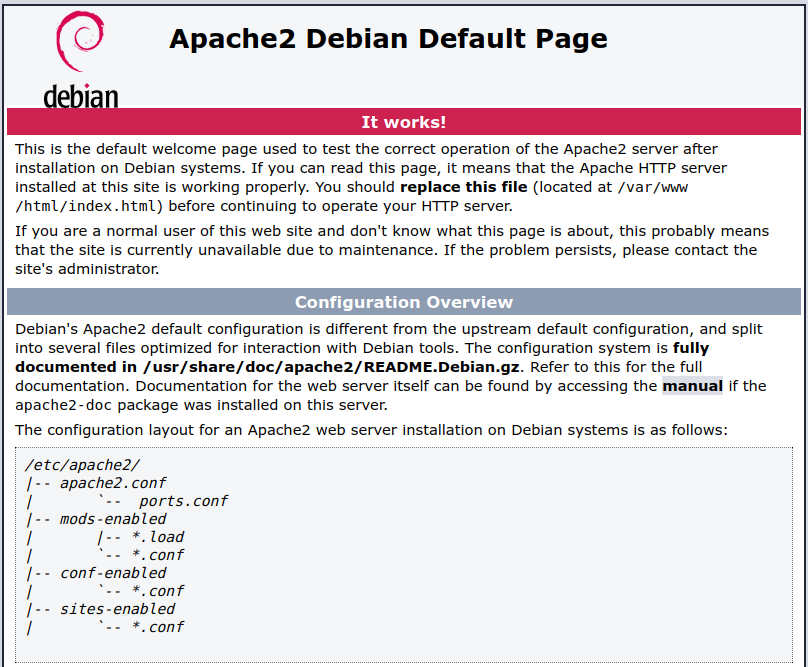

| /var/www | Default location for webpages |

(From The Linux Command Line, 2nd Edition by William Shotts.)